In this video, we’ll be talking about how to close the founder to CEO skill gap.

Hi, my name is Victor Cheng. I’m an executive coach, founder of SaasCEO.com, and the author of the book Extreme Revenue Growth. Today, what I’ll be talking about is answering this one particular question: “What separates the founders in startups that make it to CEO as a company grows and scales versus those that don’t?”

It’s a big issue in our field. A lot of private equity firms confided in me that they’re frustrated that half of their founders that they invest in need to be removed as the company grows because they can’t rise to the occasion and become the CEO that the business needs at that level. They don’t want to remove the founder. It’s just that they’re not effective anymore.

A lot of founders are very concerned that if they raise outside capital, they’re going to lose control of their business and lose their job, and sort of separate from the baby that they started. So, this is an issue everybody talks around, but nobody talks specifically about: What is the concrete difference between founders that can make it to CEO versus those who cannot? I call this difference, “The founder to CEO skill gap.”

Being a founder has a certain set of skills. Being a CEO — whether a founder that rises to CEO or being hired as an outside CEO — has a different set of skills. I want to talk about what those differences are, and how you can, if you want to, close the gap from a founder to being a CEO.

Founders have a lot of strengths. They tend to be visionary, they’re great at being innovative, they have passion, they’re frugal with capital, and they really champion the company culture. They’re fabulous at that.

CEOs are quite different. Their skills are focused around what I call “scale-relevant skills.” At $1 million in sales, that’s one kind of business. At $30 million in sales, that’s a different kind of business. CEOs have skills that become increasingly relevant as the company gets bigger. They tend to be more structured, very disciplined.

There’s a time and place for all these skills. What I want to talk about today is: How do you close these two skill gaps?

The best companies with the highest valuations, the highest returns on investments for the investors are those with founders that are able to rise to the occasion and close that founder to CEO skill gap.

Now, the premise of my talk today is that to scale your revenues, you must scale your skills as the leader of your company. It’s just not realistic to expect your business to double, triple, quadruple in size when your skill level doesn’t change during that entire time. So, that’s the premise of our talk today.

Let’s dive into it.

The Founder to CEO Skill Gap

There are about a dozen skills that founders lack and need to learn on their path to becoming CEO. I’m going to talk today about the four most common skill gaps that I see most often in the founders that I work with.

Skill Gap #1: Decision-Making Approach

Founders and CEOs make decisions quite differently. Let me explain.

Founders tend to be visionary, intuitive, and opportunistic. So, when a founder goes into a brand new market that has not yet emerged with a brand new company, there’s nothing to see. It’s literally a blank piece of paper external to the company.

If you look at the company’s metrics, there are no metrics because the company doesn’t yet exist. So, you really need, at this stage, vision. You’ve got to see what’s possible, what’s going to emerge in the marketplace and get ahead of it. You want to see what’s possible within your company and get ahead of that. So, there’s a lot of sheer determination, vision, and willpower. It’s super, super important in the early stage.

Plus, you have to have great intuition. There’s nothing to analyze in an emerging market and in a brand-new company. So, founders need to be intuitive. And they need to be opportunistic because you don’t yet know what is going to work. You have to try lots of different things.

Founders tend to say, “Yes, yes, yes.” They see an opportunity; they go after it. That’s their instinct.

CEOs, however, are a little bit different. They’re much more pragmatic. They don’t care as much about changing the world as making the quarter. They’re much more data-driven.

If you think about it, it makes sense. As you get into the mid-seven figures, and especially as you get into the eight- and nine-figure businesses, there’s a lot more data to be analyzed. CEOs, as a group, tend to be much better at analyzing data. That’s important because as the business grows, it’s too hard to manage just by looking around and looking over people’s shoulders — which is what a lot of founders typically are used to.

Finally, CEOs tend to be much more strategic. What I mean by that is that strategy is about making tradeoffs. You can’t do everything. There is an opportunity cost to every decision. Every yes means many different nos. So, CEOs as a group, tend to be much better at saying no. They say no to a lot of things in order to say yes to the one or two things that are going to make the biggest difference.

The key point here is that neither one is better than the other. It’s more that as a business grows, the skillsets needed to run that size of business evolve over time. Early on, you want the visionary, intuitive, and opportunistic thinking. Later on, you want practical decision-making that’s very data-driven and strategic — being very mindful of the tradeoffs.

Case Study #1

I had a client — classic, classic founder who started three businesses, was starting the fourth business, and had plans in mind for the fifth and sixth businesses — who asked me to help and said, “Hey, I want your help in running these businesses better.” And so, I asked for some data around these different businesses so we can make a data-informed decision. I was sort of teaching him CEO-level skills as we were going through this process.

What’s really fascinating — this really epitomizes this difference between founder and CEO — was that the business that he was most excited about was the brand-new business that doesn’t exist yet. Because he’s a visionary, he sees things that others do not see. The business he was least excited about was the one that was the biggest.

What was happening was that this business was about $10 million a year in sales, and it had a net revenue retention rate of about 140%. What that means is that if you take all the customers in January of a calendar year, kind of add up how much they spent, and you look at those exact same customers 11 months later, in December of the same calendar year, you compare how much they spent. In a business with 100% net revenue retention, they spend the same amount. He had a business that it turned out had 140% net revenue retention.

The funny thing was when I asked him what his numbers were, he didn’t know. He had to go take a couple days, go calculate it. He emailed this to me. When I heard this number, I was shocked because 140% net revenue retention is fabulous.

If you look at companies in SaaS (software as a service), in particular, the companies that are worth over a billion dollars in market cap often have 140% net revenue retention. So, I just did the math very quickly — because CEOs do math. They do calculations. What I realized was his $10-million-a-year business was going to hit $100 million a year in roughly eight years, assuming he added no new customers and assuming the 140% net revenue retention stayed constant.

This was a big revelation for him. He did not realize that he has a business that is going to have an enterprise value probably north of $500 million in under a decade.

This really epitomized the difference between founder thinking and CEO thinking. And after I did the math with him, he got really excited about owning a business that was going to exceed $100 million a year in about eight years. That can be sped up by adding salespeople or spending more time operating the business.

I think the business had one or two salespeople, and this founder was spending probably a half a day a week running this business. Now that he saw the opportunity, he was super excited to invest more in that business.

So, this is a classic, classic example of the difference between founders and CEOs. And here’s the key takeaway in all this. As companies grow, CEO-type decision-making becomes increasingly important and eventually essential.

At a certain size, it’s too hard to manage the business purely on intuition. You don’t see everything in the business. There are multiple locations. There are multiple teams. There are multiple layers of management — people report to the people that report to you, or maybe more layers, and it becomes too complicated. The skillset of managing through data becomes an essential part of the CEO skills.

Skill Gap #2: Process Maturity

The second skill gap is what I call “process maturity.” Let me define what I mean by that.

A process is the steps taken to achieve a task or complete a task inside of a company. So, answering the telephone — or that your receptionist answers the phone — is a process. You pick up the phone, you say, “Hello, how may I direct your call?” So, that’s an example of a very simple process.

Now, all processes in a company, every piece of work, whether it’s doing quality assurance for software, generating leads, closing a deal, or onboarding a customer, all those processes can be graded on a scale of immature versus mature. I call this “the process maturity curve,” immature on one end and mature on the other end.

A classic example, just to illustrate the point, would be the example of an artist. An artist is supremely talented at producing their work, which is like Leonardo da Vinci. There’s one Mona Lisa. He’s clearly an artist. But it’s very immature from a process standpoint because Leonardo da Vinci cannot train other people to be like him. It’s too difficult. That process doesn’t scale very well.

On the other end is a factory, such as a poster-printing factory, where you can train people to print out more posters of the Mona Lisa. It scales much better. So, the key point here is that processes that are mature scale, processes that are not do not scale.

The key insight here is that you want to turn your SaaS business into a factory of sorts that produces annual recurring revenue, really attractive gross margins, and very high customer retention rates.

So, if you think about your business as a factory, on the input side of the business, you’re taking the executive team, a product, a go-to-market function (like sales and marketing), various mature processes (ideally), and capital to produce an output.

All factories have inputs. They do something with inputs, and they produce an output. In the SaaS business, those outputs are annual recurring revenue, gross margins, retention, very high net promoter scores, and very happy customers. So, inputs on one end, outputs on the other end.

Your objective is to turn your SaaS business into a factory of sorts that produces annual recurring revenue, gross margin, and high customer retention, especially doing so in a way with very consistent and predictable input-to-output ratios. So, a factory that prints posters knows how much ink they need and how much paper they need to produce how many units of the poster at the other end of the factory.

Every factory has an input-to-output ratio. So, in a SaaS business, your inputs are your people and your capital, and your product and the output are all these financial metrics.

For example, when you know that you can spend a million dollars on sales and marketing and generate $2 million of annual recurring revenue at 90% net revenue retention and you’ve done it four quarters in a row, super consistent, you have a factory, or a mature process in your SaaS business.

How Do You Determine if You Have a Mature Process?

How do you evaluate whether you have a mature process? Well, the answer is that there’s a process for that, as you might imagine.

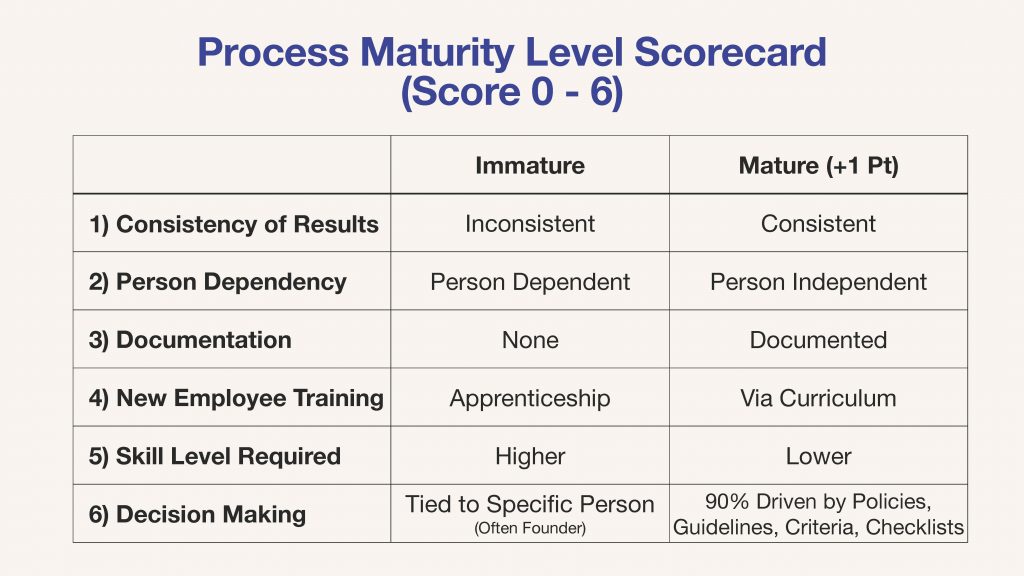

So, what I do is I like to score processes or grade them on how mature or immature they are. What I use is this process maturity scorecard that I’ve created to rate every process in the business from zero to six.

Here are the key criteria. There are six factors. And if your answer is closer to the column on the right, then you give yourself one point. If your answer is closer to the column under immature, then you don’t give yourself any points. Fives and sixes are very mature processes. Zeros are very immature processes.

Let’s look at each factor one at a time.

1. Consistency of Results

Whether this is your product development team, your dev ops, your marketing, your sales team, or your customer retention team, if your results are very consistent, there’s a very high likelihood that you have a very mature process. So, give yourself one point. If you’re inconsistent, no points.

2. Person Dependency

For example, in your customer onboarding department, does the success of those customers being onboarded vary a lot based on which specific individual in the department is doing the work? If it doesn’t matter who does the work and you still get great results, then you’re person-independent. Give yourself one point.

If there’s high volatility that if Mary does the onboarding work, compared to Bob, the customers that get onboarded by Mary do a lot better, if there’s that difference or discrepancy, that’s a person-dependent process. Therefore, it is less mature. So, it’s zero points.

3. Documentation

How do you onboard a customer? If the process by which you get work done resides in a few people’s heads, that’s an immature process because a new employee cannot come on board, read the documentation on how to do something, and start being productive. They make too many errors because they don’t know what to do. So, if you have a documented process, give yourself another point.

4. New Employee Training

Is new employee training done by apprenticeship? “Hey, just join us. Follow me around for six months. You will eventually figure it out, and then just do what I do.” That’s an apprenticeship training model. Zero points.

A more mature training model is to train people based on curriculum. “These are the 15 things we do in this role. We’re going to teach it to you, we’re going to have you practice it, and we’re going to do proficiency testing at the end of training to see if you got it. Then, we’re going to have you do your work with a supervisor who is going to watch you do your work and coach you in that first several weeks here.” That’s a more mature process.

4. Skill Level Required

Immature processes require a very high level of skill of the employees that are hired. Very mature processes can require a lower level of skill. We’ll talk more about this in a second. If you have a lower level of skill needed to be effective, then give yourself another point.

5. Decision-Making

If decision-making is tied to one specific person — such as you, the founder, or one specific person, the head of a department — and every decision is a judgment call, that is an immature process. That’s a telltale sign of an immature process.

On the other hand, a mature process looks like this: 80% to 90% of decisions are driven by policies, decision-making guidelines, criteria, and checklists. When all decision-making can be externalized out of one person’s head, and you still get the same decision — as a subject matter expert would — you have a much more mature process.

Case Study #2

Let me give you a quick example. Years ago, I had clients in a wide variety of fields and the great fortune of having clients that owned a graphic design firm, and their marquee client was McDonald’s. They were hired to revise the Hamburger University training curriculum for new franchisees that would then later be used to train new employees at new McDonald’s locations.

McDonald’s had a very interesting requirement of my former clients. They were to revise the McDonald’s training manual at Aberdeen University, but they could not use any words in any known human language on Earth. And so, what they had to do was rewrite the entire training curriculum on how to make a Big Mac using just graphics and pictures and pictograms. In other words, the Hamburger University curriculum became a lot more like an Ikea product assembly manual.

I don’t know why McDonald’s asked them to do this, but I have some suspicions. My suspicion was that they were running into a labor shortage problem. To work at a McDonald’s, you need employees that can follow instructions and read the instructions so they can follow them. They were running out of people.

So, by taking the training curriculum and removing the literacy requirement — whether that’s English or Korean or Swahili — you have the ability to take people who have a lower skill level and still have them be effective at making Big Macs. A lower skill level means a high level of process maturity. So, that’s an example of making a process more mature.

Case Study #3

My next example or case study is looking at how different kinds of businesses think about revenue.

In the software field, when a business reaches, say, $80 million a year in recurring revenue, there’s a name that gets associated with that achievement. It’s called “the unicorn.” So, a unicorn is a business with a market value of over a billion dollars. As you sort of hit that $80-million mark, people start using that term a lot to describe that kind of business. And a unicorn is just like this monumental achievement. You’ve reached the pinnacle of your career as a founder if you’ve run a unicorn business.

Now, in contrast, Starbucks has a very different word when their business achieves $80 million in revenue. That word is “Just another Tuesday.”

You see, Starbucks generates $80 million in sales every single day of the year. You never hear about it in the headlines. The reason why is because it’s a routine. It’s not a heroic effort to generate $80 million in a single 24-hour period. They do it every day. It is routine. In fact, it’s boring.

So, the difference here is process maturity. Starbucks has a process to manage all 360,000 employees they have across how many countries, I have no idea, to produce $80 million in sales every single day. That’s a high degree of process maturity.

How to Achieve Process Maturity

Let’s talk about three ways you can acquire process maturity in your business.

1. Hire Leaders with Process Expertise

If you take outside capital, one of the first things your investors will insist that you do is to fill leadership gaps. If you don’t have seasoned people in all the key functional areas, they’re going to make you hire them, recruit them to round out the team.

One of the reasons is because new leaders, especially those that have experience at the next one or two stages of growth that you have not yet achieved, when they have that kind of experience, they bring with it process maturity. So, how you manage a 100-person software development team is quite different than how you manage a five-person software development team. The amount of coordination, standardization, policies, and procedures acquired is very, very different and much more complicated as you get bigger. The same is true with marketing. The same is true with sales. The same is true with legal. Every functional area gets more complicated as you grow. So, hire outside leaders who have that process expertise.

2. Outsource

If you don’t have a great process for doing something, you want to ask yourself, “Can I just rent somebody else’s process instead?”

For example, cutting payroll checks. If you’re not really great at running a payroll process, why not hire or outsource to an ADP. They’ve cut billions and billions of payroll checks. They’re really, really good at it. They’re efficient. They have technology. It’s a very mature and sophisticated process. So, if you don’t want to create it in-house, send it and outsource it.

3. Increase the Maturity of Existing Processes

The third way is to increase the maturity of processes that are existing within the company right now. Let’s talk more about that.

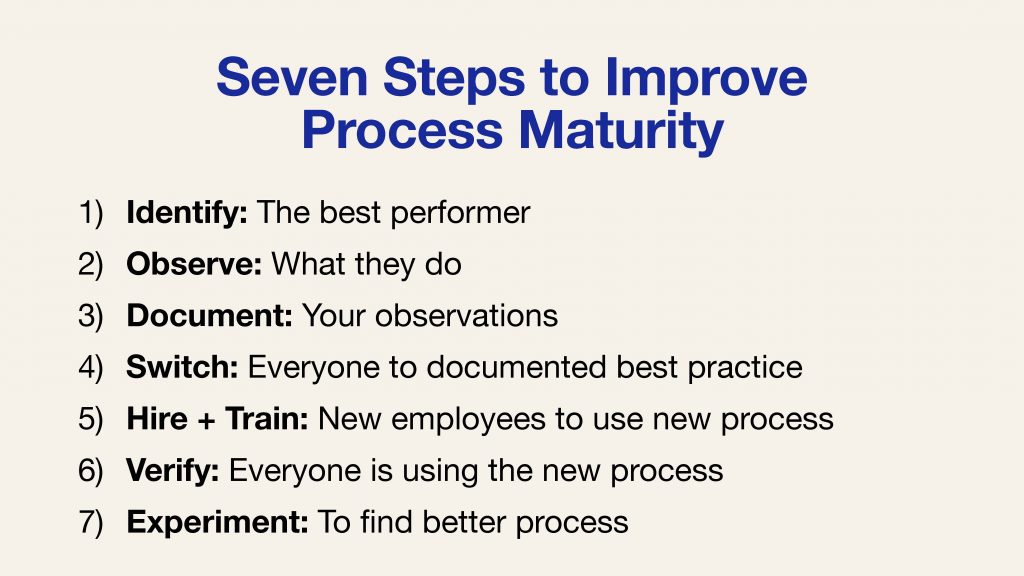

There are seven steps to improve process maturity within a specific process that you have. So, I’m gonna go through all seven steps, and we’ll talk about this a little bit more.

Step number one is to identify the best performer. I’ll give you an example. I had a client who was trying to improve customer retention and reduce customer churn. In analyzing his churn numbers, he noticed that the majority of the churn happened in the first year. When he further analyzed and broke it down by quarter, he noticed that the majority of the first-year churn with customers leaving and canceling occurred in the first 90 days. That’s a useful insight. CEOs look at the big numbers and get more specific into trying to find the root cause.

This CEO, he went even further. He looked at his four- or five-person customer-onboarding team and looked at the retention rates of the new customers that went through these various different employees. What he noticed was that there was quite a bit of variance. One person on that team performed a lot better than the other three or four. The new customers that were onboarded by one individual tended to have a much better retention rate than the others. And so, he was super curious. So, he did step one of this process. He identified the best performer on a team.

The second thing he did was observe: What did she do differently than the other people on the team? Once he figured that out, he documented those findings. And then, you want to switch everyone on that team to the newly documented best practice.

Step five is to hire and train new employees to use this process that is now documented, that is proven to work. And step six is to verify everyone is using the new process. Just because you’ve figured out what works better, don’t assume everyone’s going to immediately embrace it, you need that verification process. This is the core six steps of improving a process.

The seventh step is to experiment — to take one or two people on your team, to try to find a better way of doing things, to find the next person that outperforms everybody else. And then you repeat the first six steps all over again.

I’ll give you the insight from my client. What he noticed was that the onboarding specialists that outperform all others — at least in this particular industry for this particular company with these kinds of customers — asked one question that the other three to four onboarding specialists did not. She asked the customer, “What is your goal? What do you want to accomplish with our software? What would be a good win that if we achieved the next 30 days, you would be thrilled?”

Then, what she would do is she would simplify the training process to just teach the customer how to achieve his or her objective. All the other onboarding specialists were not asking about the goal and were teaching the customer how to do everything in their very sophisticated, very complicated software.

What my client figured out was, customers don’t like feeling overwhelmed. And so, the majority of customers were feeling overwhelmed by the power of what the software could do, and they didn’t know where to start. It was too much. So, what they did to get rid of that feeling of discomfort, of being overwhelmed, is they cancelled the software subscription.

This doesn’t mean this always works. It doesn’t mean it’ll work in your business or your industry, but it’s something to test. More importantly, they have this process of experimentation, finding your winners, your process winners that are more effective, and then standardizing across them. So, these are the seven steps to bring process maturity to any process, and this is an essential CEO-level skill.

Skill Gap #3: Disciplined Execution

So, we talked about the decision-making process as our first skill gap. Our second skill gap was process maturity. Now let’s talk about the third skill gap I see between founders versus founders that make it to CEO, and that is disciplined execution. Let me define what I mean by that.

Disciplined execution is the art and science of getting things done in an orderly way with consistent quality, quantity, and timing. So, here’s the question: “How do you create that disciplined execution in your business?” Well, the answer is, there’s a process for that, too.

Are you seeing a theme here? There’s a process to do these high-level skills. Let’s talk about that.

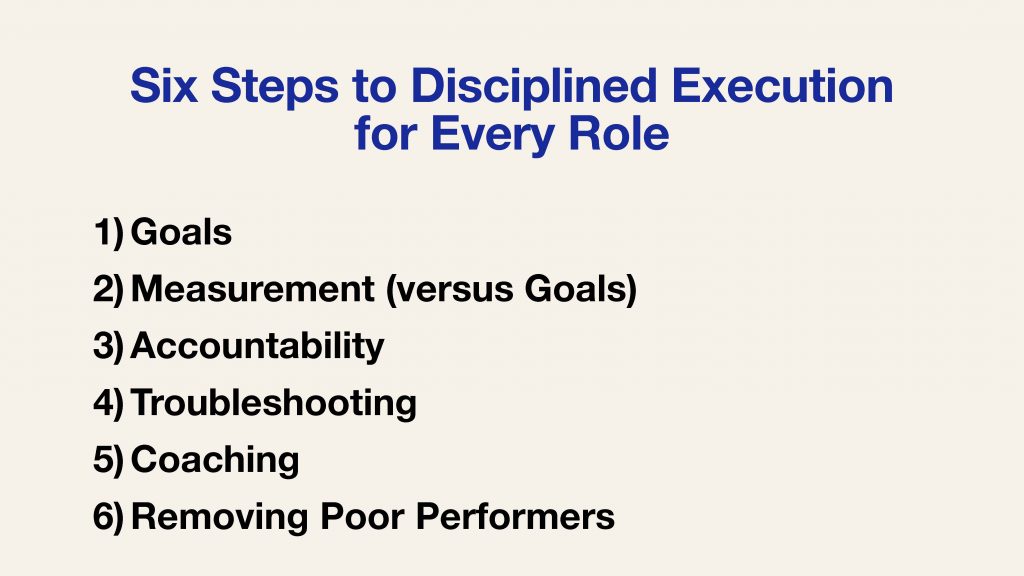

There are six steps to creating disciplined execution for every role in your company.

The first thing you need are goals. Every role in your company requires a goal.

Now, imagine if you hired a bunch of archers, and you don’t give them targets with bullseyes to aim toward. If you don’t give them something to aim for, you have no reasonable expectation that they should hit it. They’ve got to know what they’re aiming for or what they’re trying to accomplish.

The second thing you need is measurement. You need some way to tell your employees how close they are or are not to their goals. So, if you have salespeople, they need a quota. If there’s no quota, don’t expect them to hit it. And if they have a quota but you don’t tell them what they’ve closed, they’re kind of flying blind.

It’s like having a bunch of archers with a target in front of them, and then you blindfold them so that if they miss, they don’t know. Did they miss to the right? Did they miss to the left? Were they too high? Or were they too low? Did they miss by a little or did they miss by a lot? That feedback loop is important, and that feedback loop only exists if there’s a measurement system in place for every role in your company.

The third step you need to do is to create accountability. When somebody misses their goal — because now it’s measured and tracked — someone else — management, executive management, the CEO — must notice. Something has to happen as a result of the miss.

If people miss their targets and nothing happens as a result, people will keep missing their targets. It’s just that simple. So, one of two things has to happen. Either step four, troubleshooting: “You missed your sales target. How come? Let’s investigate.” That becomes a very important process. Or step five, coaching: “We know what you missed. You weren’t doing it properly. Let me tell you how to do it better. You did it this way. I need you to do it that way. Here are the three specific things that are different between the way you did it versus the way I want you to do it.” That’s coaching. That too is a skill and is required in order to have disciplined execution in any particular role or any particular team.

And the sixth step is to remove poor performers. Some people are just a mismatch for the role. They can be great at something else, but not this role. So, if you identified what’s wrong, you tried to coach them, it’s not effective, you’ve got to remove them out of the role. It’s as simple as that.

Now, of this, number four is an interesting step — troubleshooting. I think a lot of founders missed this step and aren’t really great at it. Sometimes, when people miss, it’s for reasons not directly within their control.

So, I’ll give you sort of an oversimplified example. If you’re talking to your sales team and your head of sales, and you realize every employee missed their sales quota in that team, you want to ask why.

Maybe, as you investigate or troubleshoot, you realize that the Salesforce.com system wasn’t working properly, or the digital virtual telephone system was down. And so, customers could call in, but the salespeople couldn’t answer the phone for five days out of the month. They missed their sales targets because of that.

In that case, by making the salesforce accountable, they’re going to identify obstacles that are elsewhere in the company. In this particular instance, the IT team was not supporting the sales team properly. Then, you can go troubleshoot that team to see if they have goals, if there’s a way of measuring their progress against their goals, and if there is accountability when they miss their target.

One of the great benefits of having accountability and putting pressure on teams to deliver is that they will be very honest and candid about what’s getting in their way. Because of the pressure, they’re worried about getting fired, so they’re very vocal about what else is wrong in the business. It helps you fix problems that were otherwise beneath the surface and not quite so obvious.

So, this disciplined execution process either gives you great results or it flushes out the hidden problems in your company so they’re above the surface and can be dealt with rather than hidden. If you don’t hold people accountable, they won’t tell you what else is wrong, and you’ll just constantly miss for lots of different reasons and be inconsistent across the board. So, discipline execution is very, very important.

Here’s why some founders find disciplined execution difficult. A lot of people who become entrepreneurs and startup founders, they do so because they don’t want to work for ‘the man,’ which is this metaphor for this higher authority figure that makes you show up on time, do things a certain way, and doesn’t allow you to be creative. They just want you to do certain things a certain way. And then, the great irony in all this is, you become the startup founder so you don’t have to have all this rigid discipline. But if you’re successful, you now have to become the CEO that now has to impose this discipline on everybody else.

So, if you don’t like discipline, and that’s why you’re a founder, it’s very challenging to make the leap to CEO because you have to use discipline constantly, day in, day out.

Here’s why disciplined execution matters a lot. Disciplined execution leads to predictable and consistent results. This, in turn, leads to reducing risk, which leads to a higher valuation multiple.

So, the bottom line is, you make more money when there’s disciplined execution. When you have outside investors, they want disciplined execution because they’ll get a greater return on their investment. Now, you, as a shareholder, are going to benefit a lot more at a certain stage when there’s more disciplined execution in your business.

Skill Gap #4: Compensating for Weaknesses

Let’s talk about skill gap number four. So, number one was decision-making approach, skill gap number two was process maturity, skill gap number three is disciplined execution, and skill gap number four is compensating for weaknesses.

Now, good CEOs are self-aware of their weaknesses, and there are three ways to compensate for your weakness: 1) You can hire insiders to do the things you’re bad at; 2) You can hire outsiders in order to take care of those things you’re poor at; or 3) You can work on improving your weaknesses.

So, let me stop here for a second. If you are bad at certain things, every CEO is bad at something, even the successful ones. It’s not that they’re good at everything, it’s that they realize what they are bad at, and they fill their gaps in this way.

When I talk about this idea of these four skill gaps between founder and CEO, what a lot of founders have said to me after I sort of talk about this idea is, they wonder if they should continue on in their company as the leader. If you’re not great at process maturity, if the idea of disciplined execution makes you want to vomit, then you may not be the right person to become CEO of the business, and it might make sense for you to hire someone else to do that.

Or, if you are able to step back from your personal biases, maybe you personally don’t like discipline, but the role of CEO requires discipline, and so if you’re willing to let go of your past to become what the business needs now, you can also make that transition and stay on and become a founder-CEO.

So, that’s a really fundamental question. You’ve got to decide: Which path do you want? And to improve your weakness, it’s really just two steps: awareness of where you are weak and searching for some resource to compensate for where you’re weak. Whether that is you’re looking for a new hire to replace yourself as CEO, or maybe you’re weak in finance and you want to hire a CFO, or you’re weak in technology and you want to hire a chief technology officer. If that is what your weakness is, you do want to do that probably sooner rather than later.

For example, if you’re not great in finance, you’re probably going to need a finance resource earlier than other founders that have some background in finance. So, what you need and when you need it is going to be determined, in part, by what you are weak at and what you are good at. Hiring outside vendors and consultants are also other resources that good CEOs are always searching for.

And the last one is learning resources. The good CEOs are, frankly, doing all three of these. They’re constantly recruiting for new hires, they’re constantly looking for suppliers, vendors, and consultants that can fill certain gaps that they need at that moment in time, and they’re always learning new skills in order to be more effective.

Speaking of learning resources, I want to introduce you to the resource page at SaasCEO.com. If you found today’s video and presentation helpful, you’re really going to love all the resources available at SaasCEO.com/resources. Thanks for watching and have a great day.

Here are my slides from the presentation in PDF:

Additional Resources

If you enjoyed this article, I recommend joining my email newsletter. You’ll be notified when I publish other articles and helpful guides for improving your SaaS business. Submit the form below to sign up. Also, use the email icon below to share this article with someone else who might find it useful.

If you’re the founder and CEO of a SaaS company looking for help in developing a distribution channel strategy, please Click Here for more info.

How to Scale and Grow a SaaS Business