Net revenue retention (also known as the net retention rate or NRR) is a commonly used metric in SaaS companies to measure a combination of customer retention and upsell/cross-sell effectiveness with existing accounts.

The net retention rate is expressed on a percentage scale relative to revenue. It is defined as follows:

Net Retention Rate = Revenue from Accounts in Cohort at Start of Period / Revenue from Accounts in Cohort at End of Period

While many hear the term “net revenue retention” and know investors ask about it, there are quite significant math implications to NRR that most people massively under-appreciate.

Let’s start with the basics and then build up to the insightful.

First, gross revenue retention refers to your ability to keep existing customers without them canceling their subscriptions. It is a cohort-based metric. As such, you don’t include all of the customers in your SaaS business. Instead, you only include those customers who were actively paying you at the start of the period, and you compare the revenues from that specific cohort of accounts at the start of the period versus the end of the period.

If you have 100 existing customers on the first of the month paying you $1 each, and 100% of those customers are still there on the last day of the month paying you $1/month, then your gross revenue retention is 100%. (Or the same idea stated in other terminology: your gross revenue churn rate is 0%.)

Note: Gross Revenue Retention % + Gross Churn Rate % = 100%

Gross revenue retention specifically excludes upsells in the month. It only counts what existing customers were contracted for on the first of the month and whether they are still there at the end of the month.

It is also a cohort-based metric. As such, you don’t include all of the customers in your SaaS business. Instead, you only include those customers who were actively paying you at the start of the period, and you compare the revenues from that specific cohort of accounts at the start of the period versus the end of the period.

To clarify, let’s walk through an example.

In a given year, on January 31, you have 100 accounts that generate $1,000 each for that month. Your monthly recurring revenue for January would be $100,000 (100 accounts x $1,000 per account). Now, let’s fast forward to December 31 of the same year. Your revenue for December = # of active accounts (that existed in January of that same year) x $ revenue per account.

To demonstrate, here are some examples of net retention rates under a variety of scenarios.

First, assume that $100,000 monthly recurring revenue from January is the same across all scenarios below.

Cohort = Accounts that were actively paying subscription fees in January

| # Active Accounts in Cohort Still Paying in Dec | $ Revenue per Account in Dec | Dec Revenue Across All Accounts in Cohort (# Accounts x $ per Account) | Annual Net Retention Rate (Compared to Jan) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | 100 | $1,000 | $100,000 | 100% |

| Scenario 2 | 80 | $1,000 | $80,000 | 80% |

| Scenario 3 | 100 | $900 | $90,000 | 90% |

| Scenario 4 | 100 | $1,500 | $150,000 | 150% |

| Scenario 5 | 90 | $1,300 | $117,000 | 117% |

Why Does Net Retention Rate Matter in SaaS?

As you can see, the net retention rate is important because it’s a leading indicator of the revenue and profit growth potential of the business.

When a business gains revenue through a subscription-based model or repeat purchases, it is highly susceptible to churn. Often, customers subscribe or make a purchase, and for some reason, they churn out. Thus, you stop receiving payments from them. This is represented by a net revenue retention rate below 100%. In that case, revenues will automatically decrease over time.

Ideally, your business would have a net retention rate above 100%. In these cases, the high rate shows that you’re keeping customers and they’re also increasing their spending each month. If that’s the case, you could theoretically increase your revenue forever, even if you don’t acquire new customers.

As a result, SaaS businesses with net retention rates over 100% will typically receive very high valuations.

In this next example, let’s say you have 100 existing customers on the first of the month paying you $1 each. At the end of the month, all 100 customers are still there. They’ve all maintained their existing contract, thus the gross revenue retention is 100%.

However, let’s say 10% of your customers were upsold into a higher plan. They now pay $2 a month instead of $1. So from this group of customers, you started the month at $100/month. Going into next month, they are now all contracted to pay an aggregate of $110 ($100 base + $10 in upsells).

In this scenario, your net revenue retention is 110% (and your net revenue churn rate is actually a negative 10%).

Remember: Net Revenue Retention % + Net Revenue Churn % = 100%

110% NRR + (-10%) Net Revenue Churn = 100%

To help you find your net revenue, Click Here to Download my Net Revenue Template.

Okay, now that we have that out of the way, let’s get to the more interesting stuff.

Other than the fact that you get to keep more revenue, what is the big deal about net revenue churn anyway?

Generally, the higher the net revenue retention, the better. But, there’s an enormous inflection point when NRR exceeds 100%.

This is enormously important to grasp, especially if you have a SaaS business that is at or able to get to NRR over 100%.

To understand why this is such a huge deal, we have to step back for a moment to look at the math of recurring revenue businesses.

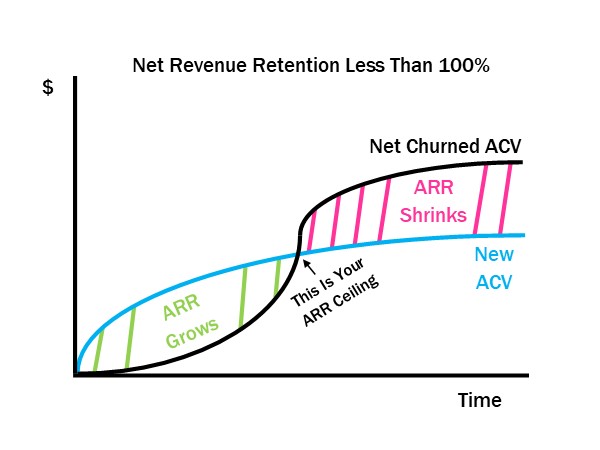

Net Revenue Retention < 100% Creates Recurring Revenue Ceilings

Recurring revenue businesses are great. You get 90%+ of your revenue every month on the first day of the month.

However, there’s a problem with recurring revenue businesses at scale. Eventually, the business gets so big that the churn dollars get enormous.

At this mathematical ceiling on the business, your monthly new bookings dollars = monthly churn dollars.

This is because, in most recurring revenue businesses, there is some revenue loss each year. If there is any revenue loss, that means that without new bookings, the revenue base shrinks over time.

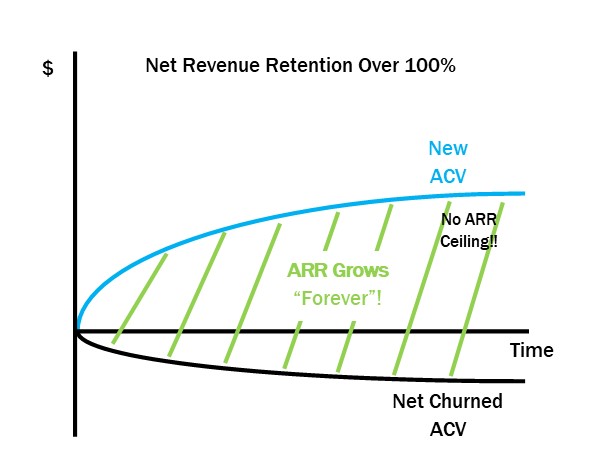

Net Revenue Retention > 100% Massively Impacts ARR

However, when net revenue retention is over 100%, there is no loss. Every initial sale not only retains but expands as well.

When you do the math, there is no revenue ceiling on the business.

This means that if you can sustain net revenue retention over 100% and you have any new bookings each month, your business will theoretically and mathematically become a billion-dollar ARR business… eventually (even if it takes 100 years).

The theoretical mathematical maximum revenue at maturity for a SaaS business with NRR over 100% is…. wait for it… infinite.

Here’s why this matters.

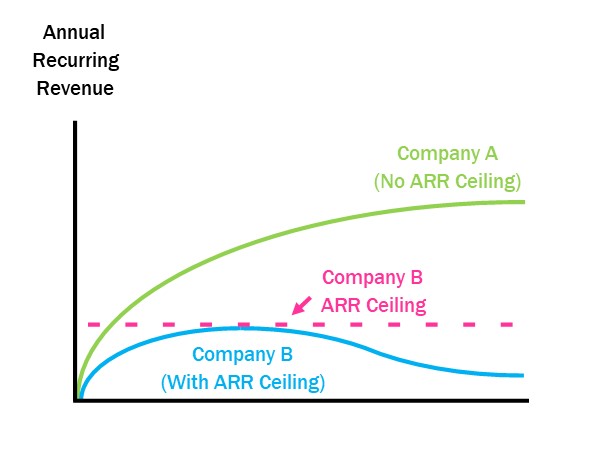

When company valuations are determined, they are determined in one of two ways (and often both ways). The first is to look at what comparable companies are selling for. The other is to build a model forecasting the company’s lifetime revenues and net income.

Intuitively, it makes sense that a business whose current trajectory never hits a ceiling is worth more than a company whose current mathematical trajectory tops out at $10 million ARR. They have wildly different economic values and thus wildly different company valuations too.

Conceptually, NRR over 100% is extremely exciting. But to really grasp why investors value this metric (especially when combined with over 100% annual growth in new ACV and high margins), you have to do the math.

To illustrate the impact of net retention rates, let’s look at a few examples.

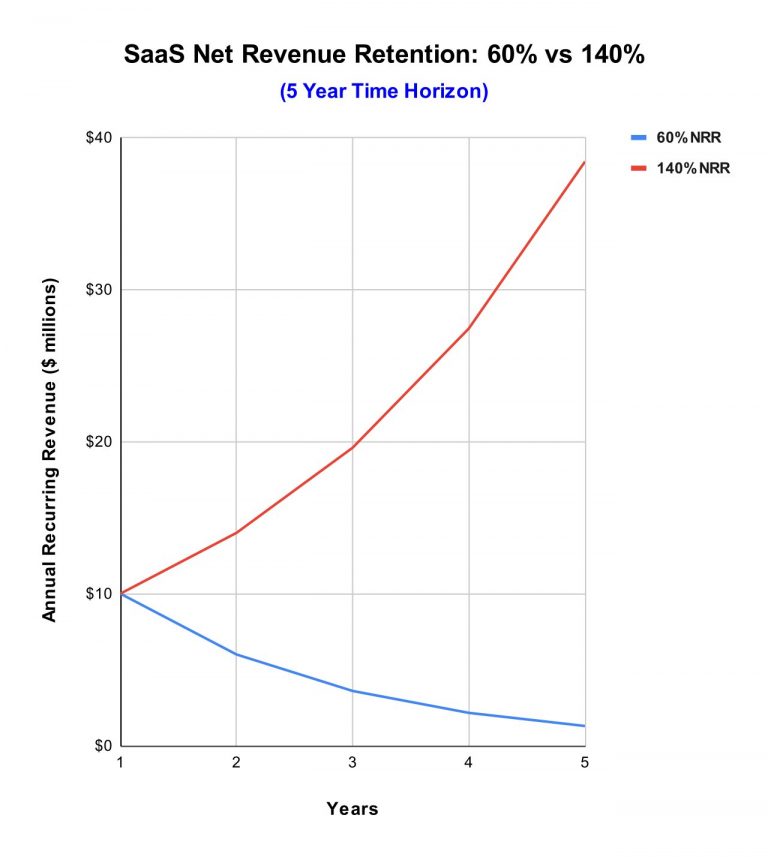

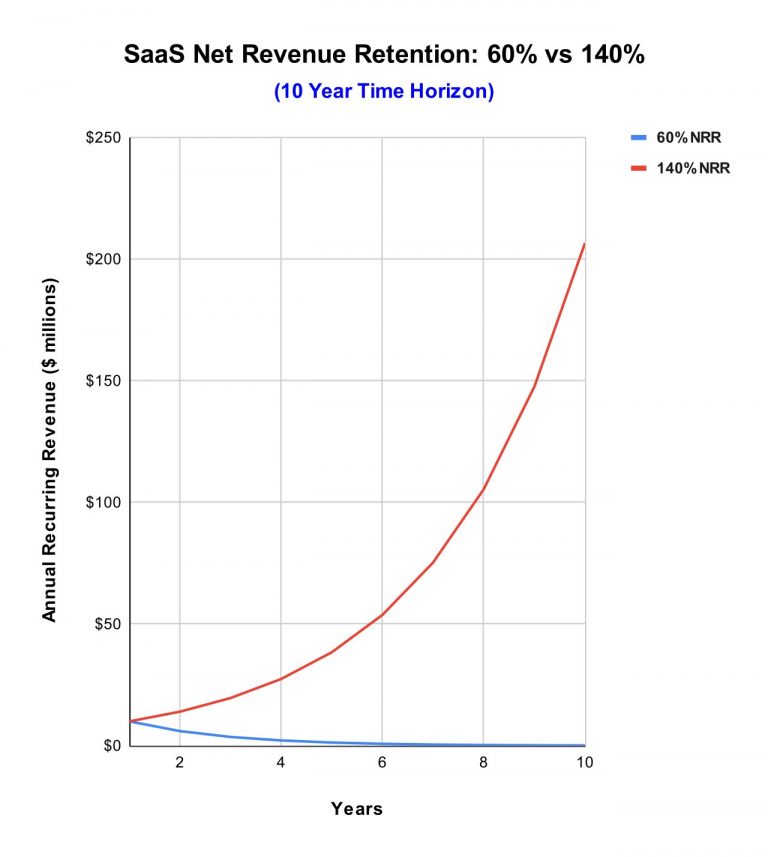

For comparison, let’s look at two businesses that each start with $10 million ARR (annual recurring revenue). Also, assume that neither business has gained new customers.

Business 1 has a 60% net revenue rate, while Business 2 has a 140% net revenue rate.

Of course, we can already tell that Business 2 is going to see more revenue growth, but let’s look at the full impact of that difference in rate.

At the end of five years, the revenue of Business 1 has dropped to just over $1 million. Alternatively, the revenue of Business 2 is approaching $40 million.

After ten years, the revenue of Business 1 continues to decrease to about $100 thousand, while Business 2 has passed the $200 million revenue mark.

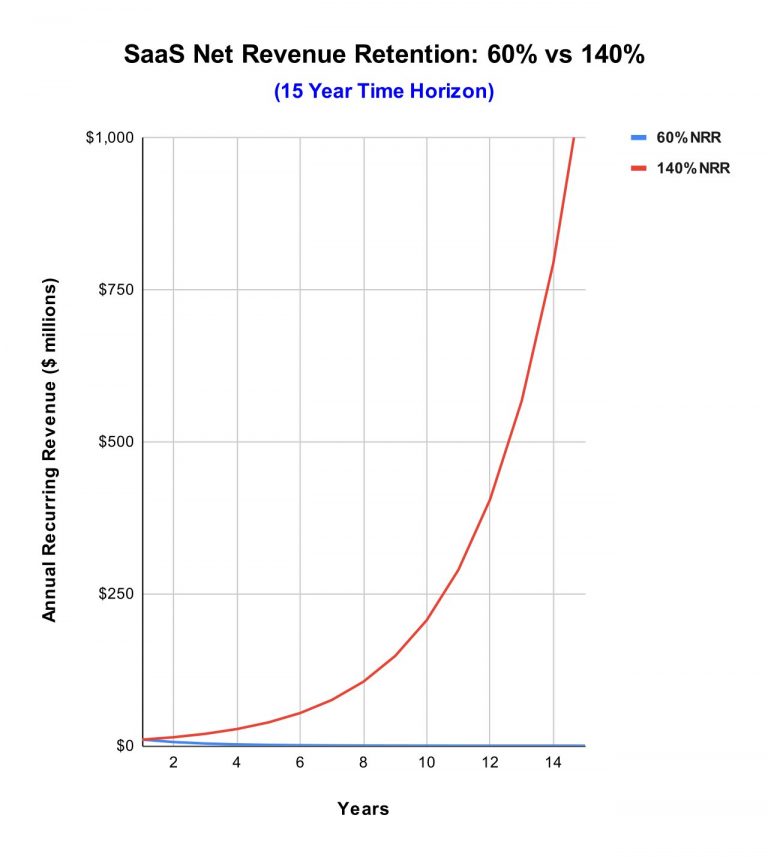

Continuing the trend of the previous charts, after 15 years, Business 1 is down to a few thousand dollars. In comparison, Business 2 surpasses the $1 billion mark.

Again, Business 2 has over $1 billion in revenue even though it has not acquired a new customer in 15 years.

Given these charts, it’s easy to see why businesses with high net revenue rates consistently gain the attention of investors. With a net retention rate of over 100%, your revenue can’t decrease, even without new customers.

In recurring revenue businesses, ARR is extremely sensitive to net revenue retention.

If you look at things from a valuation standpoint, the valuation for Business 2 is going to be a much bigger number than the same multiple applied to Business 1.

But wait… there’s more! 🙂

There’s a third-order implication to net revenue retention, which has to do with the ratio of lifetime value to customer acquisition cost (LTV/CAC).

How Does NRR Impact LTV/CAC

To put it simply, the higher the LTV, the more you can spend to acquire new customers. Companies with a higher NRR and strong sales processes can outspend competitors, and that’s an enormous advantage.

Let’s go back a bit.

The LTV/CAC ratio helps evaluate a go-to-market team’s ability to cost-effectively acquire customers. Typically, an LTV/CAC ratio of 3.0 or higher is good.

Here’s the plot twist.

You can only really calculate the lifetime value of a customer when they leave. What happens if customers never leave and, in fact, stay and spend more?

In theory, the LTV is infinite or can’t yet be determined.

So, what’s the implication for this?

Many companies try to get their customer acquisition cost down. This is totally wrong thinking. (Okay, it’s not “wrong” per se, but it is limited.)

Instead, you want to get your LTV up so high that you can tap lead-generation sources and customer-acquisition channels that your competitors cannot economically afford to pursue.

In every market, there are low-cost lead-generation channels and high-cost ones.

If your LTV is high enough, you can afford to acquire new customers through all channels, including the more expensive ones.

All of your competitors with lower LTV can only afford to compete in the low-cost lead-generation and the sales channels.

Let me give you some simple examples.

For many SaaS companies, referrals from existing customers are the lowest-cost way to acquire new customers… because there’s virtually no cost.

If your competitor has a very low customer-lifetime value, then they really can’t afford higher-cost customer-acquisition channels like paid ads, sponsorships, content marketing, outbound telemarketing, or live events.

If you have a very high LTV (fueled in large part by high net revenue retention), then you can go acquire new customers via paid ads, sponsorships, content marketing, outbound telemarketing, and live events… while they can’t.

Eventually, a company that can compete on all fronts generates enough critical mass to become the de facto standard in that market. You become the “safe choice” because everyone else is already using you. This then starts a virtuous cycle upward. Lifetime value goes up, while customer acquisition costs go down. When the LTV/CAC ratio goes up, you can afford to spend more to acquire even more customers.

Key performance metrics like net revenue retention are not just numbers you’re supposed to manage just because investors and debt lenders care about them. Metrics like NRR have relationships with other key metrics that, in turn, have enormous implications for winning in the marketplace. To be an effective SaaS CEO, you must understand these relationships and the implications they have on the outcome of your business.

This is the strategic part of being a CEO. It’s playing “chess” and seeing five moves ahead when everyone else can only see one move ahead.

NRR drives an advantaged LTV/CAC ratio… a superior LTV/CAC ratio exploited properly gives you access to corners of the market that your competitors can’t reach. In other words, when you have an LTV/CAC advantage, your TAM (total addressable market) is significantly bigger than your competitor’s.

If your competitor can only contact those prospects that their existing customers know while you can afford to contact the entire market, you will win.

Additional Resources

If you enjoyed this article, I recommend joining my email newsletter. You’ll be notified when I publish other articles and helpful guides for improving your SaaS business. Submit the form below to sign up. Also, use the email icon below to share this article with someone else who might find it useful.

If you’re the founder and CEO of a SaaS company looking for help in developing a distribution channel strategy, please Click Here for more info.

How to Scale and Grow a SaaS Business

Pingback: NRR vs. ARR - SaasCEO.com