An ideal customer profile, or ICP, defines the type of customer who is unusually well suited to buy your offering, have long-term retention, pay premium prices, be highly satisfied, and be very profitable for you. You’ll often see the ideal customer profile referenced by its abbreviation, ICP. You’ll also hear the term “buyer persona” used in a similar context.

While most SaaS founders know that they’re supposed to have an ICP and often do so to “check” an item on the “supposed to do” checklist, I’m continually surprised how 90%+ of SaaS companies under $10 million in ARR choose their ICP poorly and incorrectly.

It is not enough to have an ICP…. it has to be the correct ICP customer profile.

The key to finding the right ideal customer is to do rigorous quantitative (and qualitative) analysis. Most companies do not do this and don’t know how.

In a moment, I will share with you the step-by-step process I personally use and that I have my client and portfolio company CEOs use.

But first, there’s an important foundational concept that you need to know. Once you grasp this infrequently used concept, everything else will make a lot of intuitive sense.

The key concept is market segmentation.

The beginner version of this idea is that not all customers are created equal. Some customers really like your product. Others do not. Some types of customers churn a lot; others do not. Some customers are so demanding that they cost a lot to serve; others are super easy and require very little.

[Note: I use the terms “market segmentation” and “customer segmentation” interchangeably. Technically, market segmentation refers to grouping potential buyers in the marketplace into different groupings or segments. Customer segmentation refers to grouping actual buyers in your customer base into different groupings or segments. True market segmentation in emerging technology markets is difficult to do because there isn’t a lot of data available, and it’s expensive to conduct market research on an entire industry. As a proxy for market segmentation, I like doing prospect segmentation because it is easier to get the data. The idea is that the prospects you encounter approximate the potential buyers in the whole market. I also like doing true customer segmentation because the data is a lot more accessible.]

How Would You Create an ICP Customer Profile for SaaS?

The trick to developing a market segmentation strategy (a.k.a. finding the right ideal customer profile) is to:

- Identify the right customer segmentation pattern (this varies by company).

- Convert company-level metrics into segment-specific metrics.

- Choose a customer segment with very attractive segment-specific metrics.

[Of these three steps, almost nobody does Step #2 — converting your company KPIs into segment-specific KPIs. More on this in a moment.]

1. Identify the right customer segmentation pattern.

Customer segmentation involves both art and science. Identifying the right customer segmentation pattern is the part that starts as art and later evolves into science.

First, let’s talk about what I mean by customer segmentation pattern.

One can divide customers into different types of groupings.

A simple segmentation pattern is splitting customers into categories of small, medium, and large businesses.

The idea is that small business customers behave quite differently compared to large enterprise customers.

So, segmenting by company size is one type of segmentation pattern.

Another type is segmentation by vertical industry.

Companies that are in manufacturing behave differently than media companies. Both differ from professional service firms.

Geography is another segmentation pattern.

Customers in the United States may behave differently than customers in Colombia or Germany.

So, the first step of the process is to use your and your management team’s intuitive and qualitative understanding of the business to determine which segmentation patterns seem to identify differences in behavior.

Here’s my top ten list of customer segmentation patterns to choose and analyze:

- Company Size

- Vertical Industry

- Country

- Job Title (of Key Decision-Maker)

- Distribution Channel (e.g., Do customers sold via resellers perform differently than customers sold directly?)

- Lead Source (e.g., Do customers found via Google Ads perform differently than those found via cold calling?)

- Sales Process (e.g., Do customers who buy via eCommerce self-service perform better than customers who speak to a salesperson first?)

- TBD

- TBD

- TBD

I’ve intentionally left items eight through ten as “to be determined” because every industry and company has nuanced differences that inform the ideal segmentation pattern.

Case Study

For example, in one industry I worked in, there was a difference in buyers based on how many years they were in the industry. Buyers who entered the industry before a particular era felt biased toward the “traditional” way of doing things. Those who joined after a particular year tended to be more interested in “innovative” ways.

My client was himself an innovative personality-type trying to sell to innovative customers. However, further analysis determined that innovative customers tended to churn a lot. Ironically, when analyzed, the traditionalists (who wanted to be innovative but felt intimidated and afraid) were actually the customers who had very strong long-term retention.

Once this insight was numerically proven, the company focused exclusively on the traditionalists and even renamed the company to appeal to that segment. They revamped and optimized everything in the company for that segment. The traditionalist segment then became the company’s ideal customer profile.

Normally, I would not consider the number of years in an industry to be a likely variable by which to run a customer segmentation analysis. But in this case, the client intuitively noticed that many of his company’s best customers had been in business a long time and were technical novices.

Once you have a list of roughly ten candidates for segmentation patterns, you can switch to the science part of the process.

2. Convert company-level metrics into segment-specific metrics.

Once you have a list of segmentation patterns you think might reveal differences in behavior and performance, you need to test these hypotheses with quantitative analysis.

There are two types of analysis to run. The first is a “share of business” analysis. The other is taking your company metrics and breaking them down into segment-specific metrics.

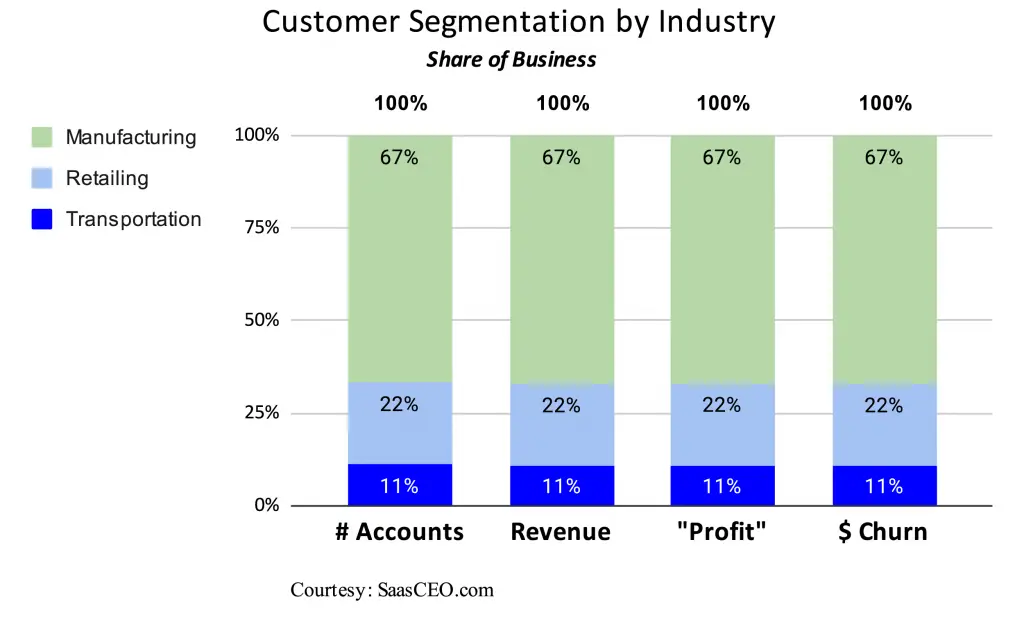

Here is an example of a share of business analysis.

Each of the stacked bars below represents 100% of the metric in question. Each of the bars in the stack represents a particular segment.

Share of Business Chart — Multiple Examples

This chart shows the market share of each customer segment in terms of the number of accounts in the customer base, revenues, profits, and churn.

In this scenario, each segment’s performance in revenues, profits, and churn is exactly proportional to the percentage of accounts the industry represents in the customer base. For example, transportation represents 11% of accounts, 11% of revenue, 11% of profit, and 11% of churn.

Each segment is exactly proportional.

I’ve been doing this analysis since my days serving Fortune 500 clients at McKinsey, and I can tell you that in the real world, the share of business chart is never exactly proportional (when you find the right customer segmentation pattern).

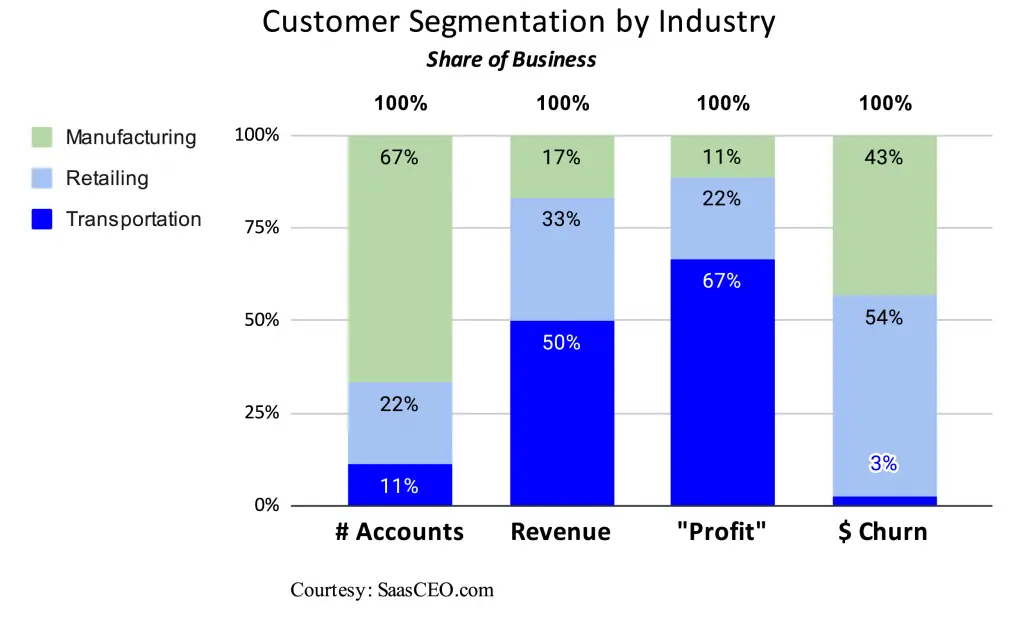

The example below is far more common:

In this version of the chart, the first thing we notice is that not all segments are created equal. The pattern is all over the place and definitely not proportional.

Let’s look more carefully to see what’s going on here.

What you’re looking for is a segment that delivers financial performance disproportionately higher than its share of the customer accounts.

More specifically, you want to look for a segment whose share of revenue is greater than the share of accounts in the company.

You also want to look for a segment where the share of profits generated by the segment exceeds its share of the revenue. Finally, we want a segment whose share of churn is much lower than the percentage of accounts in the company.

In this example, we see that one segment, the transportation vertical, meets these criteria.

Customers from the transportation industry represent only 11% of customer accounts. It’s a small segment from this perspective. However, this segment generates a whopping 50% of the revenue and 67% of the profit. When you look at the negative performance metrics like churn, this segment which is 11% of accounts represents only 3% of churn. For this particular company, the transportation vertical looks attractive.

It’s the one segment that performs disproportionately higher than its share of accounts.

Based on this analysis, the transportation vertical segment is a strong candidate for the ideal customer profile. It represents roughly 10% of accounts, half of the revenue, and two-thirds of the profit. What if we focused exclusively on this vertical? We put all the revenue and marketing dollars toward going after this ideal customer. Instead of 10% of the customers, we transition the company so that it represents, say, 100% of the customers. This would mean a dramatic increase in sales and profits — often without significant incremental investment.

[The reason for this is that one would remove expense dollars and staff currently focused on underperforming segments and reallocate those resources to the ICP segment.]

[Note: There are times when a segment seems very attractive from a share of business analysis but choosing the segment for an ideal customer profile would not be a good idea. This occurs when a segment is shrinking, in crisis, or becoming obsolete. This can also occur when the segment is very small, the company already has close to 100% market share in the segment, and there are no more customers to get. This is a “total addressable market (TAM) is too small” issue. However, in my experience, eight times out of ten, the segment that does well in the share of business analysis ends up being the right segment to pursue as the ideal customer.]

Segment-Specific Metrics

With segment-specific metrics, you’re looking for a segment that is performing really well whose performance is masked because it’s lumped into the overall company totals.

When I teach students business statistics and analysis, I tell them that totals and averages lie. You cannot trust metrics like sales, profits, churn, or net promoter scores taken at the company level. You must look at these metrics at a segment or more detailed level.

For example, I’m a shareholder of Berkshire Hathaway. I took my kids to Berkshire’s annual shareholder meeting. One of my kids wanted to see where Warren Buffett lives. Yes… I Googled his address and found it. We went for “a walk” on his street, and we may have taken a selfie with Buffett’s house “inadvertently” in the background.

As you may have heard, his home is quite modest (for a billionaire) and located in a modest neighborhood. I can confirm this to be true. My kids were like… the richest person in the world (at the time) lives there?

Now, if you look at the total net worth of every homeowner on the street, it’s hundreds of billions. If you look at the average (mean) net worth of every resident on the street, it’s multiple billions. However, as you might intuitively grasp, this is very misleading. Warren Buffett’s financials skew the analysis.

This is why anytime you see a total for a company (or a street), you need to deconstruct the metric into its component parts to get the insight.

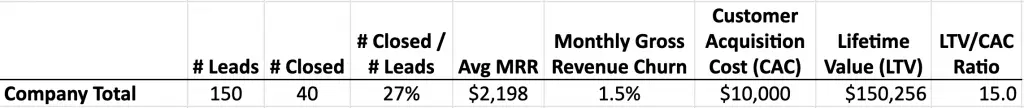

A typical set of company key performance metrics looks like this:

Overall, this company looks decent. The LTV/CAC ratio (lifetime value/customer acquisition cost ratio) looks attractive. Spending $10,000 to get a customer that produces $150,256 is a good return on investment. At the $2,000 MRR level (which suggests that this company is selling to small- and medium-sized businesses), a monthly gross revenue churn of 1.5% (or roughly 18% annualized) is reasonable.

However, as I’ve said, averages and totals lie. To figure out what’s really going on, you want to “double click” or “drill down” on the company totals to look at the customer-segment-specific metrics that comprise the company total.

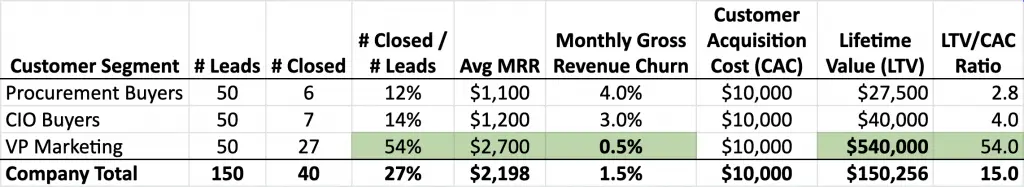

By doing so, we get the following set of metrics:

In this example, we used the job title of the primary contact of each customer as our segmentation pattern. The general impression of various team members is that when we sell to a VP of marketing, we seem to do well. However, when we sell our SaaS offering to a procurement professional or someone from the CIO’s office, we don’t do as well.

This hunch or intuitive guess suggests which customer segmentation pattern we should use to investigate further.

In this example, we see that the hunch is indeed spot on. The # Closed / # Leads conversion rate when selling to VPs of marketing is about four times higher than the other segments. VP of marketing customers spend more than twice as much. The big “show me the money” insight is in the churn rate. VP of marketing customers churn at 0.5% compared to 3.0% to 4.0% for the other segments.

This translates into a whopping difference in lifetime value. VP of marketing buyers have a lifetime value of $540,000, which is about 13.5 to 20 times higher than the other segments.

When you look at the overall company LTV/CAC ratio, it was already a very solid 15. However, when you look at the LTV/CAC ratio at the segment level, you see that the ratio is a ridiculously attractive 54.0 for the VP of marketing segment.

Now, of course, these metrics are for a fictitious company. I’ve exaggerated the metrics to make a point. And my point is that you must deconstruct your company-total and company-average metrics into segment-specific metrics.

3. Choose a customer segment with very attractive segment-specific metrics.

Once you see the metrics at a segment level, you need to make a judgment call as to which segment to focus on as your ideal customer profile. Here are some examples:

Example 1:

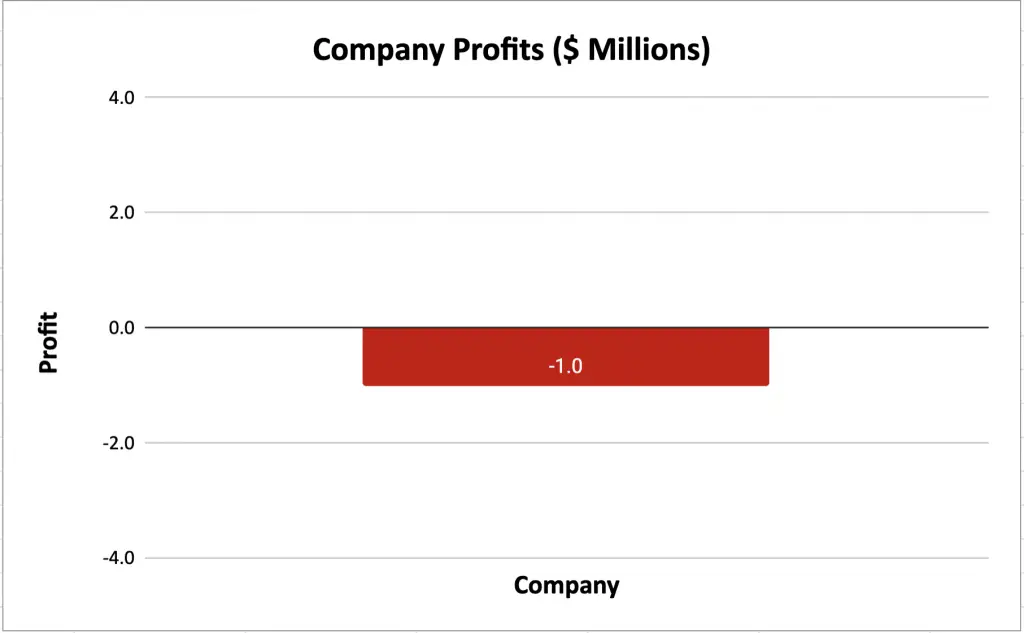

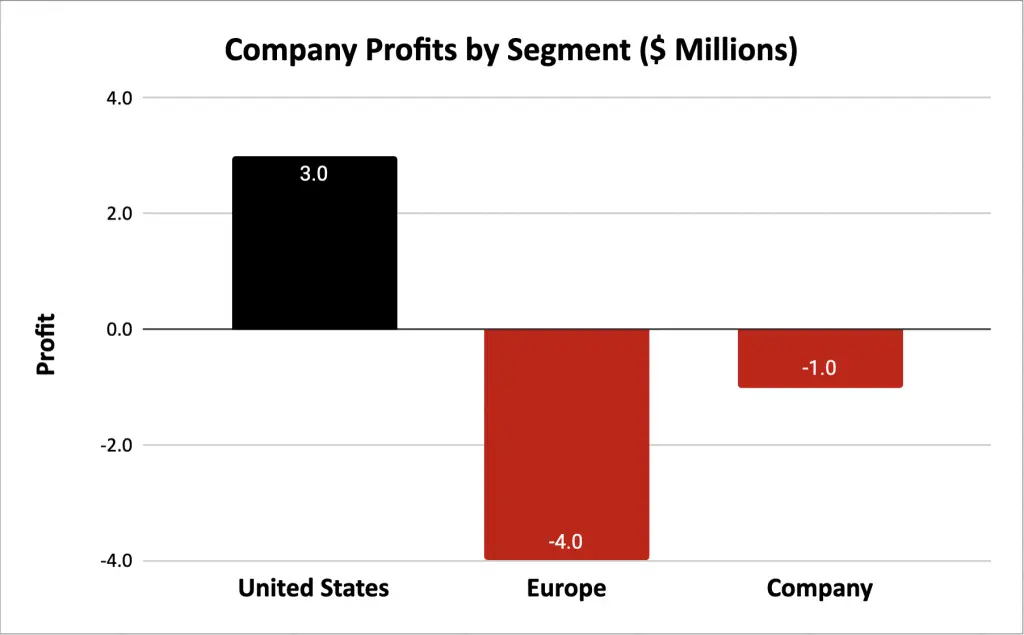

Let’s say you have a business with $10 million in sales, but it’s losing money. Profit = -$1,000,000. This would not be surprising in the SaaS startup world.

At face value, this business is losing money.

But let’s say you decide to segment the customers in this business, and you find that there are two geographic segments — the United States and Europe. Each segment comprises 50% of sales, or $5 million each.

The United States contributes $3 million to profits.

Europe contributes a $4 million loss to profits.

If you look at company profits overall, you don’t see the whole picture.

When you break down the profits into the customer segments that make up the profits, it reveals a lot more insight.

This would be a very insightful fact to understand.

This isn’t a -$1M business at all. This is actually a company with two “businesses.” One “business” is highly profitable. The other loses a lot of money.

It would make sense to explore whether the entire ICP acronym business should focus around the United States, with buyers in the United States being the ideal customer profile.

[Note: This isn’t the only analysis you would do to make such a determination. There may be other factors at play here, including which segments are growing versus shrinking and looking at whether the segment-specific unit economics (such as profit per customer) causing losses in Europe may be driven by front-loading expenses to drive growth in later years.]

Example 2:

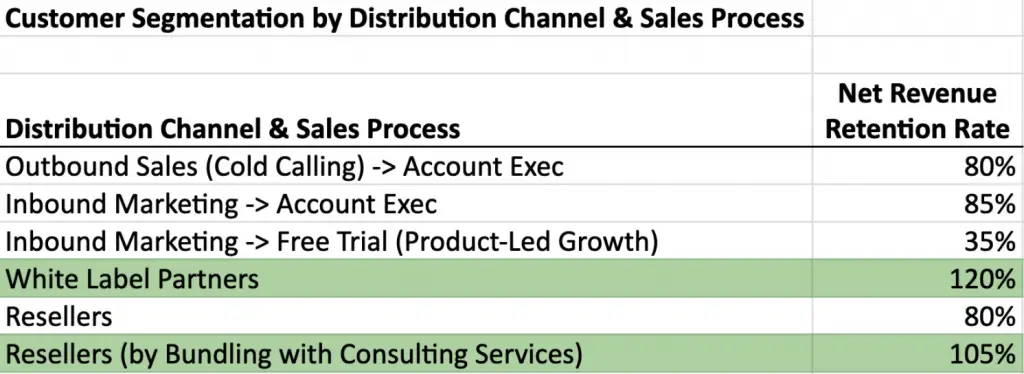

As you know, churn and customer retention both make huge differences in the long-term economics of a SaaS business. Most companies know their overall company churn and net revenue retention rates. However, I’m surprised how few calculate and track churn or net revenue retention by customer segment.

Here’s an example graph showing how that difference can be significant:

Making the Final Ideal Customer Profile Decision

You start the selection process for an ideal customer profile with intuition. You test your intuition against segment-specific analyses. You end the process by looking at all the analytical data and making a decision. On which segment do you want to bet the company?

At the end of the day, it’s a data-informed judgment call. Most founders skip the data part of the process.

Timing Considerations

A brand-new startup will not be able to run data analysis because there is not yet any data. When you start from scratch, you go off your best guess of who is willing to buy. In the early days, the key is to start capturing good data that you can analyze down the road.

You can usually get a sense of sales traction within a few months. Getting at least a directional indicator of churn tendencies will often take a few quarters.

Multiple Customer Segments

Sometimes, you will have one or more customer segments that are equally attractive in different ways. Which one should you pursue? If the segments are adjacent to each other, it may be possible to serve more than one segment. If you can serve the needs of the two segments with the same product, same marketing, and same sales team, selling to more than one may work.

However, if the segments diverge in their product requirements, best lead-sourcing strategies, and vary dramatically in the distribution channels or sales processes needed to close, diluting focus across multiple divergent customer segments can be a significant problem.

A lot of founders want to serve everyone. After all, why limit yourself, right?

The problem is resources. There are only so many dollars to go around. Similarly, there is only so much talent and attention. If you have $400 million in cash on your balance sheet, yes, you can focus on multiple segments. If you don’t, you’re going to have to pick and choose.

Ideal Customer Profile — Decision-Making Angst

When you have one customer segment that stinks and another that’s fantastic, it’s easy to kill off the one that stinks.

What’s psychologically much harder for founder CEOs is when you have three or four “good” customer segments but only one “exceptional” one.

It is very difficult to kill a good opportunity and a good customer segment. However, in a resource-constrained environment, to invest big in the exceptional customer segment, you must be willing to reallocate resources from the merely “good” customer segments.

One dollar in marketing spend produces different returns across different customer segments.

One dollar in sales spend produces different returns across different customer segments.

One new hire produces different returns across different customer segments.

To get the maximum return and growth, you must be willing to bet big on the exceptional customer segment.

Additional Resources

If you enjoyed this article, I recommend joining my email newsletter. You’ll be notified when I publish other articles and helpful guides for improving your SaaS business. Submit the form below to sign up. Also, use the email icon below to share this article with someone else who might find it useful.

If you’re the founder and CEO of a SaaS company looking for help in developing a distribution channel strategy, please Click Here for more info.

How to Scale and Grow a SaaS Business

Pingback: How To Use An Ideal Customer Profile In B2B Marketing?

Pingback: Here's How to Make Generating Targeted Leads Simple - Trustmary

Pingback: SEO For SaaS: Actionable Advice On B2B SaaS SEO Success! | Serps Growth