In SaaS businesses, you see a lot of acronyms. This article focuses on two specific acronyms: ARR and NR. They are often used in the same context but have very different meanings. I’ll cover the differences between ARR and NRR, what each metric means, and why they’re important.

ARR stands for annual recurring revenue.

NRR stands for net recurring revenue.

Let’s discuss what each one means and in what context you’d use them.

ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)

ARR, or annual recurring revenue, refers to a specific dollar (or other currency denomination) amount of your revenues that came as a result of some kind of subscription or recurring contractual obligation.

Here’s an example:

Let’s say your SaaS startup generated $20 million in revenues in your last fiscal year.

- $12 million of that revenue was from software subscriptions.

- $4 million of that revenue was from transaction fees associated with your service. (Think: an SMS texting software service where your customers pay a fixed amount per month to access the service and a per–message fee for each message sent. The per-message fee would be considered “transaction revenue.”)

- $4 million of that was consulting fees to help new customers migrate to your technology.

In this example, your business would have $12 million in ARR, or annual recurring revenue, for the prior fiscal or calendar year (depending on the timeframe one references or implies with their usage of the term).

Sometimes, a company will make a forecast of the annual recurring revenue.

An example might be:

Last year, we generated $12 million in ARR. For this coming year, we are on pace to hit $17.5 million in ARR for the full calendar year. We also have an ARR run rate of $24 million for the full calendar year.

In this context, “on pace to hit $X million in ARR” is a forecast of the results that management thinks they will hit by the end of the year.

In this context, “ARR run rate” typically refers to the most recently completed month’s monthly recurring revenue, or MRR, multiplied by 12 (months).

The “on pace to hit $X million in ARR” and the ARR run rate will differ for companies that are either growing or shrinking quickly.

For a given calendar year in a growing business (without any weird seasonality), January sales are usually lower than December sales. The full calendar year expected or forecasted ARR is based on the combination of each month’s monthly recurring revenue added up. A full-year forecast would include the actual MRR for the months that have already transpired and an estimate of the expected MRR for the remaining months of the year. Adding up each month’s actual or estimated revenue from recurring contracts gives the expected or forecasted ARR.

Your monthly revenues for the current year might look like this:

Your forecasted/estimated/expected ARR would be the recurring revenue actually generated or expected to be generated in each month of the year. In this case, the forecasted ARR would be $17.5 million.

The ARR run rate takes the most recent month’s revenue from recurring contracts and multiplies it by 12. So, if your company did $2 million in recurring revenue in December of the year in question, $2 million x 12 months = $24M ARR run rate. “We expect to hit a $24M ARR run rate in December of this calendar year.”

NRR (Net Recurring Revenue)

NRR, or net recurring revenue, is a type of financial analysis used to assess two key capabilities of a company:

- Ability to retain customers (and prevent them from “churning” out of the business)

- Ability to upsell/cross-sell existing customers

When customers and their revenues “churn,” this reduces revenue for the business.

When customers are upsold or cross-sold additional products and services, this increases revenue for the business.

These two factors offset each other. The NRR, or net recurring revenue, metric is used to assess which of these offsetting factors is larger.

Do more customers leave than can be offset by the upsells/cross-sells from the customers who remain? Or did the opposite occur?

NRR is measured in percentages.

An NRR of 120% means that when you take baseline revenues (which I’ll define in a moment) at the start of the analysis period (typically 12 months), subtract churned revenue, and add in upsells/cross-sells, the revenues at the end of the analysis period are 20% higher than those at the start of the period.

An NRR of 100% means that when you take baseline revenues at the start of the analysis period, subtract churned revenue, and add in upsells/cross-sells, the revenues at the end of the analysis period are exactly the same as those at the start of the period.

An NRR of 80% means that when you take baseline revenues at the start of the analysis period, subtract churned revenue, and add in upsells/cross-sells, the revenues at the end of the analysis period are 20% lower than those at the start of the period.

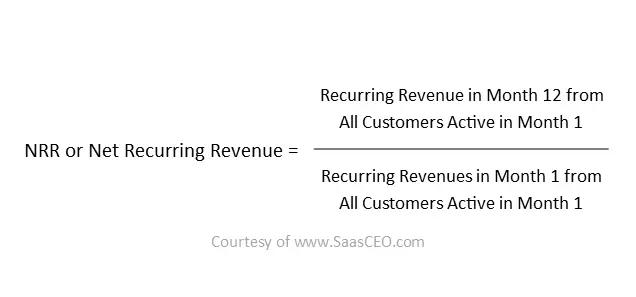

Below is the formula for calculating NRR, or net revenue retention, for a given 12-month period (can be for a calendar year or the prior 12 months, such as March 2023 to Feb 2024).

When to Use ARR vs. NRR (and Why)

Because ARR is measured in dollars (or euros), you use ARR when you want to see how big a company is (regardless of whether the growth comes from new customer acquisition, keeping existing customers, or selling more to existing customers).

A company with $1 billion in ARR is substantially larger than a company with $10 million in ARR.

You use NRR when you want to see how well a company retains customers and upsells/cross-sells to the customers it retains. This is an incredibly useful metric for determining if you have a business that is effective at keeping and growing existing customers. However, because NRR is measured in percentages (comparing Month 12 revenues to Month 1 revenues), NRR does not tell you about the size of a company.

For a company with an NRR of 140%, you have no idea if the company has $10 million or $1 billion in sales. You just know they’re really, really good at keeping customers and selling more to them.

What NRR does tell you is the growth potential of a business. A business with 140% NRR that can keep performing at that level will eventually be a very large business. You just can’t tell from NRR alone if they are at the start of that growth trajectory or much further along.

As an example, most unicorn SaaS companies (businesses with a market valuation over $1 billion) often have an NRR in the 140% range.

Venture capital firms that specialize in growth-stage businesses and private equity firms that invest in or buy companies capable of explosive growth look at NRR to determine the business’s growth potential.

These same entities look at ARR to see how big the company is and whether or not the company size is within the range of their investment criteria.

(For example, many private equity firms are prohibited from investing in companies with less than $10 million ARR or more than $X ARR. This is typically determined by the firm’s investment strategy and the size of its fund. They don’t want to put their entire fund into a single investment for a company with ridiculously high ARR. At the same time, they don’t want to invest in too many small firms, as it’s the same amount of work to invest in a $1 million ARR company as it is a $10 million ARR company.)

To see how NRR impacts future revenue growth via charts and graphs, see my article: Net Revenue Retention — Why it Matters a Lot

Additional Resources

If you enjoyed this article, I recommend joining my email newsletter. You’ll be notified when I publish other articles and helpful guides for improving your SaaS business. Submit the form below to sign up. Also, use the email icon below to share this article with someone else who might find it useful.

If you’re the founder and CEO of a SaaS company looking for help in developing a distribution channel strategy, please Click Here for more info.

How to Scale and Grow a SaaS Business

Excellent stuff. Well explained, Thanks Victor!

Really interesting – Thank you